The Buddhists did not deliberately misrepresent their tradition or just tell the Americans what they wanted to hear. They were genuine in their attempt to make a 2500-year old tradition relevant to the late 19th century.

Sakya Monastery of Tibetan Buddhism, Seattle, Washington.

Wonderlane, CC BY

Pamela Winfield, Elon University

In East Asia, Buddhists celebrate the Buddha’s death and entrance into final enlightenment in February. But at my local Zen temple in North Carolina, the Buddha’s enlightenment is commemorated during the holiday season of December, with a short talk for the children, a candlelight service and a potluck supper following the celebration.

Welcome to Buddhism, American-style.

Early influences

Buddhism entered into the American cultural consciousness in the late 19th century. It was a time when romantic notions of exotic Oriental mysticism fueled the imaginations of American philosopher-poets, art connoisseurs, and early scholars of world religions.

Transcendental poets like Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson read Hindu and Buddhist philosophy deeply, as did Henry Steel Olcott, who traveled to Sri Lanka in 1880, converted to Buddhism and founded the popular strain of mystical philosophy called Theosophy.

Lorianne DiSabato, CC BY-NC-ND

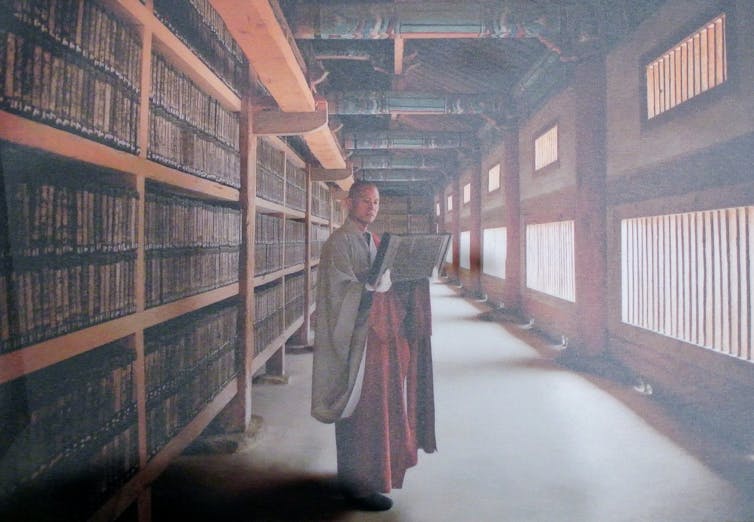

Meanwhile, connoisseurs of Buddhist art introduced America to the beauty of the tradition. The art historian and professor of philosophy Ernest Fenellosa, as well as his fellow Bostonian William Sturgis Bigelow, were among the first Americans to travel to Japan, convert to Buddhism and avidly collect Buddhist art. When they returned home, their collections formed the core of the premiere Arts of Asia collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

At the same time, early scholars of world religions such as Paul Carus made Buddhist teachings readily accessible to Americans. He published “The Gospel of Buddha,” a best-selling collection of Buddhist parables, a year after attending the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. This was the first time in modern history that representatives from the world’s major religions came together to learn about one another’s spiritual traditions.

The Buddhist delegation in Chicago included the Japanese Zen master Shaku Sōen and the Sri Lankan Buddhist reformer Anagārika Dharmapāla, who himself had studied western science and philosophy to modernize his own tradition. These Western-influenced Buddhists presented their tradition to their modern Western audience as a “non-theistic” and “rational” tradition that had no competing gods, irrational beliefs or supposedly meaningless rituals to speak of.

Continuity and change

Traditional Buddhism does in fact have many deities, doctrines and rituals, as well as sacred texts, ordained priests, ethics, sectarian developments and other elements that one would typically associate with any organized religion. But at the 1893 World Parliament, the Buddhist masters favorably presented their meditative tradition to modern America only as a practical philosophy, not a religion. This perception of Buddhism persists in America to this day.

The Buddhists did not deliberately misrepresent their tradition or just tell the Americans what they wanted to hear. They were genuine in their attempt to make a 2500-year old tradition relevant to the late 19th century.

But in the end they only transplanted but a few branches of Buddhism’s much larger tree into American soil. Only a few cuttings of Buddhist philosophy, art and meditation came into America, while many other traditional elements of the Buddhist religion remained behind in Asia.

Buddhism in America

Once it was planted here though, Americans became particularly fascinated with the mystical appeal of Buddhist meditation.

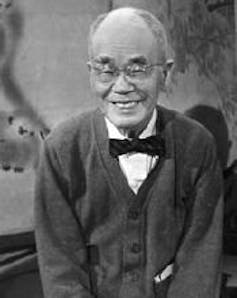

Portrait of D. T. Suzuki made by his secretary Mihoko Okamura via Wikimedia Commons.

The lay Zen teacher Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki, who was Japanese Zen Master Shaku Sōen’s student and translator at the World’s Parliament, influenced many leading artists and intellectuals in the postwar period. Thanks to his popular writings and to subsequent waves of Asian and American Buddhist teachers, Buddhism has impacted almost every aspect of American culture.

Environmental and social justice initiatives have embraced a movement known as “Engaged Buddhism” ever since Martin Luther King Jr. nominated its founder, the Vietnamese monk and anti-war activist Thich Nhat Hanh, for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1967. His Buddhist Order of Interbeing continues to propose mindful, nonviolent solutions to the world’s most pressing moral concerns.

America’s educational system has also been enriched by its first Buddhist-affiliated university at Naropa in Colorado, which paved the way for other Buddhist institutions of higher learning such as Soka University and University of the West in California, as well as Maitripa College in Oregon.

The medical establishment too has integrated mindfulness-based stress reduction into mainstream therapies, and many prison anger management programs are based on Buddhist contemplative techniques such as Vipassana insight meditation.

The same is true of the entertainment industry that has incorporated Buddhist themes into Hollywood blockbusters, such as “The Matrix”. Even professional athletics have used Zen coaching strategies and furthered America’s understanding of Buddhism not as a “religion” but as a secular philosophy with broad applications.

The exotic appeal

Geoth

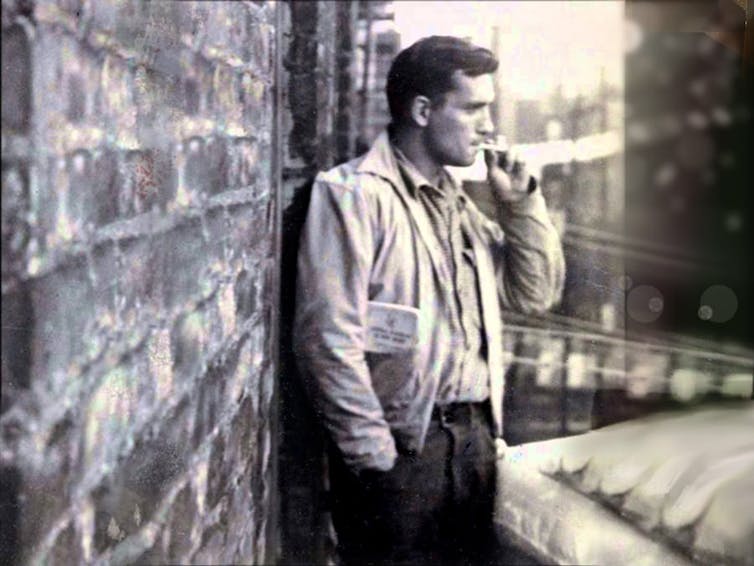

But American secular Buddhism has also produced some unintended consequences. Suzuki’s writings greatly influenced Jack Kerouac, the popular Beat Generation author of “On the Road” and “The Dharma Bums.” But Suzuki regarded Kerouac as a “monstrous imposter” because he sought only the freedom of Buddhist awakening without the discipline of practice.

Other Beat poets, hippies and, later, New Age DIY self-helpers have also paradoxically mistaken Buddhism for a kind of self-indulgent narcissism, despite its teachings of selflessness and compassion. Still others have commercially exploited its exotic appeal to sell everything from “Zen tea” to “Lucky Buddha Beer,” which is particularly ironic given Buddhism’s traditional proscription against alcohol and other intoxicants.

As a result, the popular construction of nonreligious Buddhism has contributed much to the contemporary “spiritual but not religious” phenomenon, as well as to the secularized and commodified mindfulness movement in America.

![]() We may have only transplanted a fraction of the larger bodhi tree of religious Buddhism in America, but our cutting has adapted and taken root in our secular, scientific and highly commercialized age. For better and for worse, it’s Buddhism, American-style.

We may have only transplanted a fraction of the larger bodhi tree of religious Buddhism in America, but our cutting has adapted and taken root in our secular, scientific and highly commercialized age. For better and for worse, it’s Buddhism, American-style.

Pamela Winfield, Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Elon University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Copy Protected by Chetan's WP-Copyprotect.

Copy Protected by Chetan's WP-Copyprotect.