Twitter’s been on fire with people amazed by cats that seem compelled to park themselves in squares of tape marked out on the floor. These felines appear powerless to resist the call of the #CatSquare.

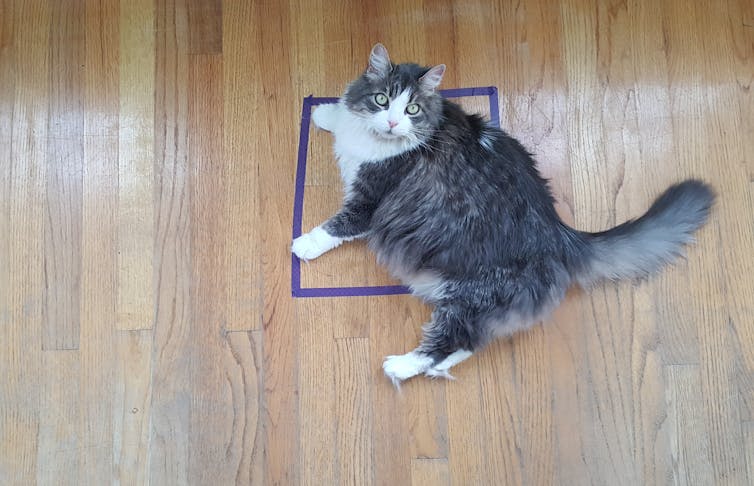

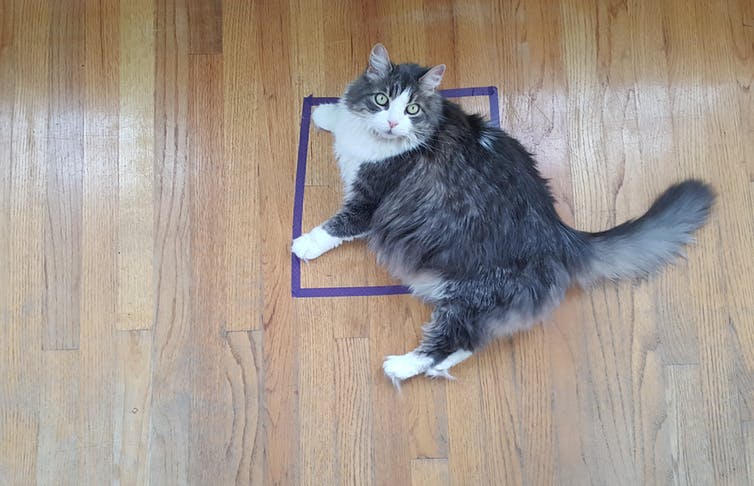

Next best thing to a hidey-hole box?

Maggie Villiger, CC BY-ND

Nicholas Dodman, Tufts University

Twitter’s been on fire with people amazed by cats that seem compelled to park themselves in squares of tape marked out on the floor. These felines appear powerless to resist the call of the #CatSquare.

This social media fascination is a variation on a question I heard over and over as a panelist on Animal Planet’s “America’s Cutest Pets” series. I was asked to watch video after video of cats climbing into cardboard boxes, suitcases, sinks, plastic storage bins, cupboards and even wide-necked flower vases.

“That’s so cute … but why do you think she does that?” was always the question. It was as if each climbing or squeezing incident had a completely different explanation.

It did not. It’s just a fact of life that cats like to squeeze into small spaces where they feel much safer and more secure. Instead of being exposed to the clamor and possible danger of wide open spaces, cats prefer to huddle in smaller, more clearly delineated areas.

Cats image via www.shutterstock.com.

When young, they used to snuggle with their mom and litter mates, feeling the warmth and soothing contact. Think of it as a kind of swaddling behavior. The close contact with the box’s interior, we believe, releases endorphins – nature’s own morphine-like substances – causing pleasure and reducing stress.

Along with Temple Grandin, I researched the comforting effect of “lateral side pressure.” We found that the drug naltrexone, which counteracts endorphins, reversed the soporific effect of gentle squeezing of pigs. Hugs, anyone?

Also remember that cats make nests – small, discrete areas where mother cats give birth and provide sanctuary for their kittens. Note that no behavior is entirely unique to any one particular sex, be they neutered or not. Small spaces are in cats’ behavioral repertoire and are generally good (except for the cat carrier, of course, which has negative connotations – like car rides or a visit to the vet).

One variation on this theme occurs when the box is so shallow that it does not provide all the creature comforts it might.

Or then again, the box may have no walls at all but simply be a representation of a box – say a taped-in square on the ground. This virtual box is not as good as the real thing but is at least a representation of what might be – if only there was a real square box to nestle in.

This virtual box may provide some misplaced sense of security and psychosomatic comfort.

The cats-in-boxes issue was put to the test by Dutch researchers who gave shelter cats boxes as retreats. According to the study, cats with boxes adapted to their new environment more quickly compared to a control group without boxes: The conclusion was that the cats with boxes were less stressed because they had a cardboard hidey-hole to hunker down in.

Lisa Norwood, CC BY-NC

Let this be a lesson to all cat people – cats need boxes or other vessels for environmental enrichment purposes. Hidey-holes in elevated locations are even better: Being high up provides security and a birds’s-eye view of the world, so to speak.

![]() Without a real box, a square on the ground may be the next best thing for a cat, though it’s a poor substitute for the real thing. Whether a shoe box, shopping bag or a square on the ground, it probably gives a cat a sense of security that open space just can’t provide.

Without a real box, a square on the ground may be the next best thing for a cat, though it’s a poor substitute for the real thing. Whether a shoe box, shopping bag or a square on the ground, it probably gives a cat a sense of security that open space just can’t provide.

Nicholas Dodman, Professor Emeritus of Behavioral Pharmacology and Animal Behavior, Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, Tufts University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Copy Protected by Chetan's WP-Copyprotect.

Copy Protected by Chetan's WP-Copyprotect.